PURGING HISTORY AT NCBC

Mainstream Churches are at once both conscious and unconscious of themselves. They are conscious of the image they project onto a society where religion is often portrayed as stuffy dated and inconsequential, and yet they are also unconscious of their own image-consciousness.

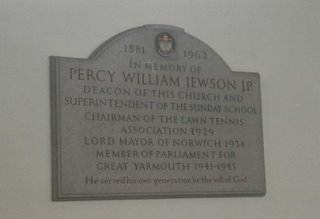

Take for example, the recent merger that resulted in the formation of Norwich Central Baptist Church. NCBC occupies the site of a historically prestigious local church whose foundation goes back to pre-enlightenment times; 1669, in fact. Before its recent renovations, the walls of the church were graced with paintings, old photographs and memorial stones celebrating the lives of past Baptist grandees and their positions both in church and society (See photos). Some members of the newly formed NCBC, however, felt uncomfortable with the rather starkly formal surroundings of the 1950s built church. My guess is that the display of solemn looking grandees and memorials was part of the problem. During renovations the pictures disappeared and there was even talk of removing the stone memorials. The bust of Joseph King-Horn, one of the church patriarchs, which dominated the Deacons room, also mysteriously disappeared. In fact a split in the vacated wooden base of the bust gives the appearance of it having been removed with some force! Although I don’t think this is actually the case, nevertheless, when I examined the empty pedestal I was sharply reminded of the broken stone to be found in the empty niches of medieval churches that suffered at the hands of zealous puritans! The comparison here may be a little strained, but one thing we can be sure of: once again the goal posts of religious perspectives are on the move and contemporary Christains no longer feel comfortable with the icons, images and expressive modes of a bygone time.

Take for example, the recent merger that resulted in the formation of Norwich Central Baptist Church. NCBC occupies the site of a historically prestigious local church whose foundation goes back to pre-enlightenment times; 1669, in fact. Before its recent renovations, the walls of the church were graced with paintings, old photographs and memorial stones celebrating the lives of past Baptist grandees and their positions both in church and society (See photos). Some members of the newly formed NCBC, however, felt uncomfortable with the rather starkly formal surroundings of the 1950s built church. My guess is that the display of solemn looking grandees and memorials was part of the problem. During renovations the pictures disappeared and there was even talk of removing the stone memorials. The bust of Joseph King-Horn, one of the church patriarchs, which dominated the Deacons room, also mysteriously disappeared. In fact a split in the vacated wooden base of the bust gives the appearance of it having been removed with some force! Although I don’t think this is actually the case, nevertheless, when I examined the empty pedestal I was sharply reminded of the broken stone to be found in the empty niches of medieval churches that suffered at the hands of zealous puritans! The comparison here may be a little strained, but one thing we can be sure of: once again the goal posts of religious perspectives are on the move and contemporary Christains no longer feel comfortable with the icons, images and expressive modes of a bygone time.

NCBC senses that the current cultural climate no longer favors the ecclesiastical and traditional trappings that encrusted the Baptist faith of the past. Church members seem non-plussed about the meaning of these overt and shameless displays of Baptist tradition and I can’t help but be reminded of the ruinous stone iconography of ancient Egypt whose power to invoke any sense of religious seriousness has long since gone because their mystique was bound up with their social context. Take a close look at the paintings and pictures of those Baptist patriarchs that once proudly hung on the walls of the Old Duke St. Baptist church: the demeanor and dress of these men signal anchorage, solidity, stability, tradition, experience, civic connection, scholarship, all of which seem inappropriate in fluid times of fast moving media images, disaffection and societal changes capable of rendering a life time’s experience void. Moreover, this religious memorabilia harks back to an era that had more confidence in secular government and was proud of civic status. Contemporary government no longer presumes a consensus and has more the character of a collection of pressure groups whose raison-d’etre of agitation are found in the fragments of postmodernism’s ‘little narratives’. In that process churches have become yet another marginal pressure group, often alienated from the secular civic authorities that once had a Christian gloss. Churches are therefore less able to identify with government and less willing to celebrate their civic connections, unlike their Christian predecessors.

As it is with the fragmentation of governmental vision so it is with theoretical visions. Grand narratives, like grand authorities, are taken as a sign of didactic presumption. These days you don’t let on if you have an all-embracing theoretical vision giving you the where-with-all to comment on anything, because that just comes over as intellectual hubris. The Postmodern vision does not accept that we live in a world sufficiently coherent to allow that sort of thing - the miracle of a cognitively integrated world is “pie in the sky” (Ironically that is precisely what it is!). Thus do churches feel uncomfortable with a confident modernist approach and they tend to make concessions to the ambiguities, diffidence, and downright nihilism of the day. The contemporary church is unlikely to make much of its claim to being the steward of an all-embracing theoretical cosmic vision and instead sells its feminine caring side, making show of primeval human traits such as relationship, love, music, feeling, adoration, and personal connection. These are values that few would dare to gainsay, as they seem to be the last bastions of humanity as the cold of a heartless cosmos seeps in. Not for the first time in history, then, there is a swing toward a touchy-feely romanticism in reaction against the hell like vision of an unfeeling machine world. At its most extreme this retreat into one’s humanity takes the form of a gnostic conversion to spiritual mysticism and fideism, a conversion that makes the recipient open to exploitation by shamanistic authoritarian demigods such as we find in the charismatic cults. It is surely an irony that those rather stuffy looking but scholarly genteel Baptist patriarchs, often vilified for being six feet above contradiction in their high pulpits, should now be replaced by apostles of anti-reason who take a dim view of so much as a probing question, let alone contradiction, and demand an unthinking fideism that rubbishes any investigation of their work as a sign of the unbelief of man’s reason.

Traditional ways are often discarded like outdated clothing and sometimes with the affected abhorrence that pubescent offspring show toward their parent’s styles and outlook. True, there is wisdom in this reaction in as much as it refreshes outmoded practices and language. But injustice is done if this also entails a forgetfulness of the past and a failure to acknowledge the good work of those who have gone before. I am not arguing for the formal portraits and Kinghorn’s bust to be prominently and dominantly displayed at NCBC – times have changed and we are here to serve the present and not the past. However, I can’t help but be suspicious of the motives behind the quiet disappearance of certain historical artifacts from NCBC. Does it betray a failure to come to terms with our past? Churches are often uncomfortable with one another and may even be alienated from each other (See previous post) so it comes as no surprise if churches are alienated from their own histories. In fact they often haven’t come to terms with some of their own members; there is sometimes a gap between an aspired church self-image and what is actually the case, and this can lead Christains to turn on one another demanding that they conform to this or that blessing, this or that renewal, this or that doctrine, this or that church structure, this or that preacher man, this or that prophecy, or this or that style of worship.

As for those old Baptist grandees, their own iconography has done them an injustice – they come over to us as anachronisms, static museum pieces conveying a message that can be misunderstood even by Christains. But rather than contemplate their dusty memorials it is much better to read their words in, for example, back copies of the church magazine, “The Messenger”. It is then that one starts to come into contact with their personalities and one is then left in no doubt about their faith. They successfully carried the flame for a while: as one Christian Blogger has put it using the words of another, if eccentric, giant of faith: “We stand on the shoulders of (the) giants (of faith).” They were spiritual, even if we despise their memorials. But I suppose our opinion of them doesn’t really count. If they worked well, their work will remain long after we have gone and will outlast even their stone epitaphs. Let us pray that our work will also stand the test of eternity. (1 Cor 3:11-15).

Joe Kinghorn: Gone to the great free lunch in the sky.

Traditional ways are often discarded like outdated clothing and sometimes with the affected abhorrence that pubescent offspring show toward their parent’s styles and outlook. True, there is wisdom in this reaction in as much as it refreshes outmoded practices and language. But injustice is done if this also entails a forgetfulness of the past and a failure to acknowledge the good work of those who have gone before. I am not arguing for the formal portraits and Kinghorn’s bust to be prominently and dominantly displayed at NCBC – times have changed and we are here to serve the present and not the past. However, I can’t help but be suspicious of the motives behind the quiet disappearance of certain historical artifacts from NCBC. Does it betray a failure to come to terms with our past? Churches are often uncomfortable with one another and may even be alienated from each other (See previous post) so it comes as no surprise if churches are alienated from their own histories. In fact they often haven’t come to terms with some of their own members; there is sometimes a gap between an aspired church self-image and what is actually the case, and this can lead Christains to turn on one another demanding that they conform to this or that blessing, this or that renewal, this or that doctrine, this or that church structure, this or that preacher man, this or that prophecy, or this or that style of worship.

As for those old Baptist grandees, their own iconography has done them an injustice – they come over to us as anachronisms, static museum pieces conveying a message that can be misunderstood even by Christains. But rather than contemplate their dusty memorials it is much better to read their words in, for example, back copies of the church magazine, “The Messenger”. It is then that one starts to come into contact with their personalities and one is then left in no doubt about their faith. They successfully carried the flame for a while: as one Christian Blogger has put it using the words of another, if eccentric, giant of faith: “We stand on the shoulders of (the) giants (of faith).” They were spiritual, even if we despise their memorials. But I suppose our opinion of them doesn’t really count. If they worked well, their work will remain long after we have gone and will outlast even their stone epitaphs. Let us pray that our work will also stand the test of eternity. (1 Cor 3:11-15).

Joe Kinghorn: Gone to the great free lunch in the sky.

No comments:

Post a Comment